I am delighted to introduce this month’s poet: Jean Stevens. We have met several times over the last two years on writing workshops – all on Zoom.

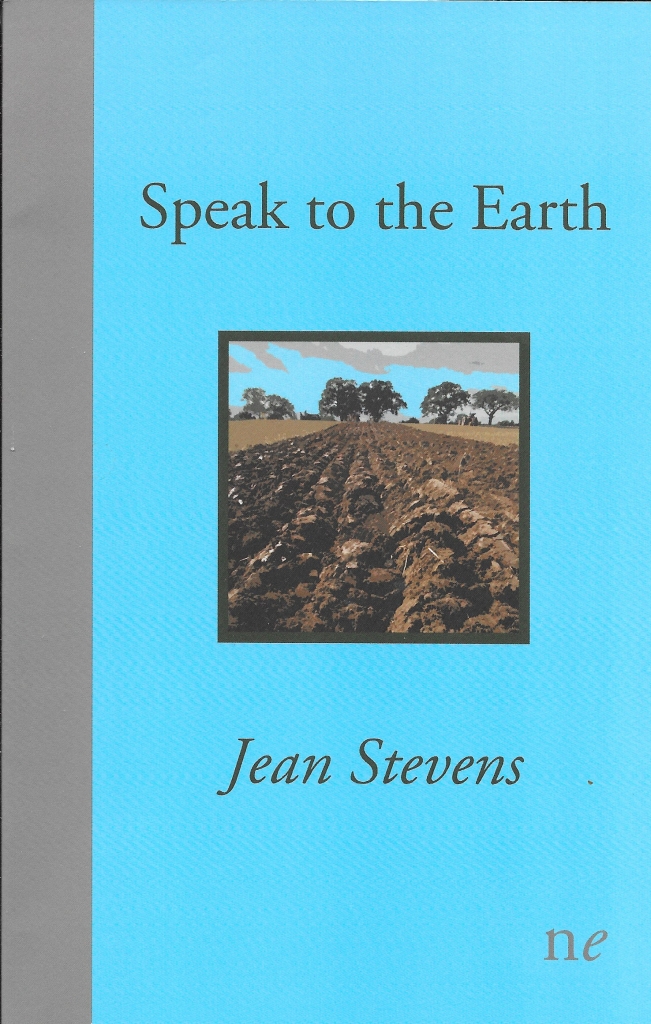

Jean Stevens’ poems have been widely published in magazines and newspapers and broadcast on BBC Radio 3 and Radio 4. She is a past winner of Leeds Libraries Writing Prize and was shortlisted for the Bridport Prize in 2020. Her most recent poetry collections are Speak to the Earth (Naked Eye 2019) and Nothing But Words (Naked Eye 2020). Her forthcoming collection Always Too Many Miles will be published in 1922, also by Naked Eye.

Jean has worked as a professional actress and dramatist and her stand-up comedy script won the Polo Prize at London’s Comedy Store.

The collection Speak to the Earth is in five sections and I have chosen one poem from each.

Night safari

At the Singapore Night Safari, animals roam freely in moonlight

in environments replicating their lives in the wild. Visitors and animals

are separated only by the slimmest of man-made divides.

I walked the rainforest’s moonlit trail

and found myself among leopards.

They were lean, honed by hunting

and hunger and, as flesh and muscle

ebbed and flowed, I saw

down to the beat of blood

and the almost liquid bone.

Their skin was a print of their own

dark paws walking on sand,

their flanks were brandy and treacle,

brown ale held to the light.

I knelt by the narrow divide

and a leopard lay opposite,

mirrored light in his midnight eyes.

He didn’t blink and I was held

till he stretched and showed his claws.

I turned to the man who stood next to me.

We’re nothing he said.

Hefted

Hefted : accustomed and attached to an area of upland pasture.

It’s cloistered in the depths of the valley

inside this old house, where cellos

have left echoes in the stone,

poets’ words are carved in the beams,

and the bones of cattle lie under slate

but one day I will follow the hefted sheep

out of here through clear northern light

to climb the far hills and beyond to where

there are no buildings, no roads, no noise

except the battering of the wind.

Drama school

Drama schools are fond of sending students

to the zoo to study the behaviour of beasts.

It’s what people laugh at when they speak about

the ‘luvvies’: be a cat, be a dog, be a bloody giraffe.

But look, Lear’s on his knees and clawing Cordelia.

His hands are paws and he’s mauling her body

round the stage, frantic to revive her.

He’s done the mad scene in the storm

railed against every roof

cried: Never, never, never, never, never.

Now he makes us see what we all are

at heart: animals learning to grieve.

Gagudju man

Remembering Bill Neidjie (‘I’m telling you this while you’ve got time’)

This was the man who shared

the long-held secrets of his world.

I met him in Alice Springs, sat with him

in the aboriginal silence, knowing

his closeness to every living thing.

He felt trees in his body,

their trunks and leaves pumping water

as human hearts pump blood,

thought that no matter what kind –

kangaroo, eagle, echidna –

animals pulse in our flesh,

said, if you harm what is sacred,

you might get a cyclone or flood,

or kill someone in another place,

told us we must hang on to the land,

the trees, the soil, because of the day

when we become the earth.

Waking

I wake to bed linen strewn

around like manic laundry

and can’t get out of my head

the creatures I dreamt of

who eat only fruit and leaves

and gaze at the beings

who hack down trees, ravage

land, sea and air, blast their kind

off the earth, and bring silence,

the silence of the animals.

On my way to meet the morning

I’m desperate to hear the bleating

of sheep, the trill of blackbirds,

a dog barking after a stick,

but nothing moves, nothing speaks.