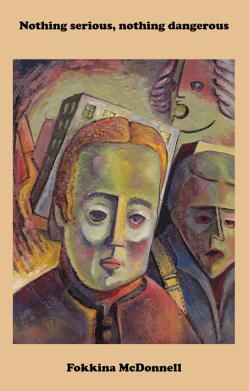

Tomorrow is the publication date of my second collection Nothing serious, nothing dangerous. The book is already on Amazon and has been available for pre-publication orders from Indigo Dreams Publishing.

The publishers have selected six accessible poems for the author page, and the author photo is by my nephew Ted Köhler who lives in the Netherlands and is beginning to build up a photography portfolio. The end of November is too close to the festive season for an official launch. That will be here in Manchester, at the International Anthony Burgess Foundation on Tuesday 3 March.

The title was inspired by a Raymond Carver poem called My Boat. Raymond Carver is one of my all-time favourite poets. Someone I return to when I feel stale and in a negative frame of mind.

The poem Why are we in Vietnam? was written on a workshop at the wonderful Almassera Vella, Spain. We were to find any book in the library, open it at random and use a few lines as a starting point for a poem. Then we were to imagine finding a postcard inside the book. Where was the postcard from? What was written on the back? Who had sent it? I picked the paperback because of its intriguing title. It’s by Norman Mailer. I was surprised to find the lines and I imagined there would be an art card inside, a card I’d bought and forgotten about. It’s a reminder how working with “found” materials can easily trigger our creativity. The poem was commended in the 2016 Havant Open Poetry Competition.

Why are we in Vietnam?

It has held up the broken leg

of a single bed in the attic.

Everything is dusty now.

Who brought this Panther

paperback into my life?

Then the trail of the blood

took a bend, beat through dwarf alder.

The postcard isn’t of Cezanne’s gardener

seated upright in his chair,

or Venetian gondoliers.

Didn’t want to die in those woods,

wounded caribou…

Green lines, black dots,

small yellow triangles,

Miro’s insects and birds.

Neat black lines for the address,

the black box for a stamp.

To the left white space,

the white space of that Alaska.