I’m delighted to introduce this month’s guest poet Kathy Pimlott. We met a couple of years ago on a residential workshop and are both members of a small group that meets regularly online.

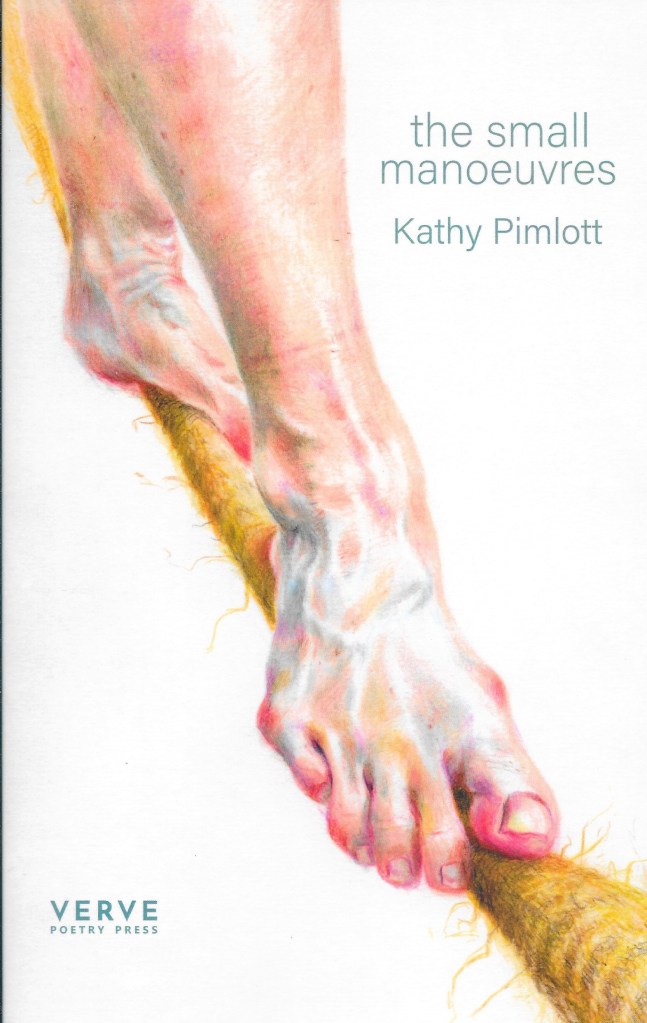

Kathy Pimlott’s debut full collection, the small manoeuvres, (Verve Poetry Press) was published in April 2022. She has two pamphlets with the Emma Press, Goose Fair Night and Elastic Glue and is widely published in magazines and anthologies. She lives in Seven Dials, Covent Garden, London.

The splendid cover is by Sharon Smart, a London-based artist (www.sharonsmart.com)

Many of the poems have intriguing titles. Here are a few examples:

- the Baby in the Wardrobe

- Three Men in a pub, probably, they made it happen

- Some Context in Mitigation

- Apple Day: An Apology

I have chosen four poems which demonstrate Kathy’s ‘immaculate eye for the juicy, telling detail’, her tender-dry wit’ (Claire Pollard). You can find more of Kathy’s work on her website here.

The Grand Union Canal Adventure

We three old girls, fractured

by the usual losses, aren’t mended

Japanese-style with precious seams

that make each fissure sing,

but rivetted: serviceable, not art.

To prove our mettle, we choose

to chug along the old Grand Union,

moor by fields of roosting geese

to sway in darkness on the water’s

shallow, dreamless shift.

Forty feet above the Ouse, I’m left.

The others go below to show me

I can, despite my doubts, skipper us

along the strait way of the aqueduct,

not falter, step back into empty air

down into the river’s wilder waters.

On a narrow boat there’s no choice

but to make the small manoeuvres

that trundle us over the drop and on,

now and again to know the satisfaction

of a perfect approach to a bend.

Shins bruised, knuckles scraped raw,

we tie up, step ashore to climb the hill

up to the Peace Pagoda, so golden,

so unlikely, outside Milton Keynes.

Small Hours

In one of the many ways I’m guilty,

I cursed my baby to a life of broken sleep,

laying my hand on her back, lovingly

rousing her to check she was still alive.

Now when I creep in in the dark to feel

her breathing on the back of my hand,

my mother stirs from her merciful sleep,

asks what time it is. For when I’m not here,

which is mostly, I bought a special clock:

press once to hear the time and once again

for day and date. But tonight I am, carry

her hearing aids to their cradle to charge.

One buzzes on my palm and I think I hear

a faraway voice, an urgent message

just out of earshot. Now that she can see

nothing by looking, all the looking things

are done with, leaving only the voices

of talking books, their complicated family

crochet work, sagas of poor girls’ privations

bravely overcome and a clock saying 3.45am.

Going to the Algerian Coffee Store: 500g Esotico

After the bin lorry has exhausted its beautifully modulated warnings,

after the glass lorry has shifted shingle, I step out into West Street

and the dog-end of last night, where a sweeper leans on his cart

and chats with his own country and a man with his trousers down

round his knees hobbles past, trailing a sleeping bag over his arm

like a negligent debutante with her stole. The pavements are tacky,

no loitering snappers, no witless number plates outside The Ivy yet,

just yellow drums of spent oil and bags of yesterday’s fancy breads

awaiting their special collections under the heritage lamppost.

In what passes for peace, helicopters and gulls are still roosting

as I skirt the grim lieutenants outside Le Beaujolais, their hybrid engine

purring as they wait for lowly envoys on stolen bikes. My age exactly,

The Mousetrap sleeps the sleep of the utterly justified. Or, I leave

by the front onto Earlham Street, its hat stall, cinnamon and falafel fug,

risk an erratic rickshaw bike’s right turn, cross the Circus, passing

the latest sensation at The Palace, into Soho’s loud and narrow scuzz

of £12 haircuts, tattooists, Aladdin, leather masks, the endless churn

of fit outs. And all the boys, the visitors, the louche remains of glory days

drink coffee on Old Compton Street, study each other side-eyed across

the blue recycling bags and natty dogs. The choice of pastries is infinite.

Weathers in the City

Our lead-laced down draughts gust

between high-rises, blow sex cards

from phone kiosks, shake plane trees

to sneezes. Not true winds as such.

Very rarely, a small dry frost or snow

will sit on rubbish sacks, out-of-town

van roofs or a still-flowering geranium,

to deliver one day of lovely hysteria

before slumping to grey inconvenience.

Or the old sun asserts itself, sets fires

in the fancy-angled glass of the City,

melting wing mirrors until, cooling,

it slinks off, faintly ridiculous. Without

oceans, rippling cornfields, crags,

we must find the sublime where we can.

Once, from the Lyric Hammersmith bar,

disappointed with the play, I looked out

and saw a triple rainbow, so clear it made

anything possible. And sometimes grubby air

rests on our cheeks as if we are loveable.